Teresa Draguicevich

Elementary Educator

helping children step into the future together

Redefining Parental Involvement

Historically, establishing the connection between home and school has proven problematic for many schools precisely because our definition of what constitutes valuable learning is narrow and our concept of the role of the home and the school in this process is rigid and outdated. So often, educators see the role of the parents as supporters for the teaching efforts of the school through school-dictated means such as homework support, participation in school events and conferences. This approach often alienates families who are not white-collar and at least middle class, not to mention families from several cultures and linguistic backgrounds. Although, this is not the intent of well-meaning educators, unfortunately it is often the result.

In Social Class Differences, Lareau (1987) compares parental involvement at two different schools and illustrates how our current approach to defining parental involvement excludes families with lower incomes. In the research study, parents at the first school (Prescott), were financially well-off, had advanced degrees and saw themselves as equal partners with teachers regarding their children’s education. They helped their children with spelling test preparation, read to them regularly, helped them practice math and were intimately aware of the inner workings of the school, especially if their child struggled with academics. As much as educators want this type of involvement, it comes with some challenges. For instance, teachers at the Prescott school reported feeling that often parent involvement meant undue stress and anxiety for the child, because of the pressures that the parents would place upon their child (p. 81). At Colton, the other school in the research study, parents had a high school diploma or were high school drop-outs. Economics was a challenge for most families, and the parents saw teachers as professionals more qualified to teach their children than they were (p. 84). They rarely attended school events or parent teacher conferences, asked few questions about the curriculum and did not provide extra tutoring or support at home if their child struggled with spelling tests, reading or math skills. Teachers at this school desperately hoped for more involvement from parents. I have worked with both types of parents over the years and have often wished that I could get the Prescott parents and the Colton parents together to learn from each other.

My greatest concern with the study begins with its definition of parental involvement that matters. Although Lareau brings up several interesting points, she fails to ask what I see as the critical question. Why are we defining parental involvement and support for a child’s education within the narrow parameters of the often inauthentic assignments that schools ask parents to oversee and support? By prioritizing spelling tests, homework packets and test scores, the school often inadvertently guides parents’ attention in directions that create panic in parents with advanced degrees. They end up feeling that if their child does not ace every aspect of second grade, for instance, then their child will drop out of college and end up homeless on the streets! Their often subconscious panic translates into stress for the child from the undue pressure. In addition, parents who struggled in school, were alienated because of inequitable teaching environments in their own childhood or who have limited English end up feeling ill equipped to support their children with homework or to partake in parent conferences where vast amounts of non-contextualized English is used. Although unintentional, this formula for connecting home and school through teacher-directed, artificial learning usually ends with parent panic or parent withdrawal.

To make things worse, some researchers subscribe to the culture-of-poverty thesis, which states that lower-class culture has distinct values and forms of social organization that lack support for education. Lareau explained that although their interpretations vary, most of these researchers suggest that lower-class and working-class families do not value education as highly as middle-class families (as cited in Deutsch, 1967). This toxic thinking often permeates the walls of the school without our conscious awareness of it. In addition, it seems that research has looked at the impact of a family’s socioeconomic level and culture negatively for the cause of the obstacles to creating strong connections between the school and the parents, focusing on what parents in lower socioeconomic neighborhoods don’t do. For instance, according to Tough (2006), “In the professional homes, parents directed an average of 487 “utterances” — anything from a one-word command to a full soliloquy — to their children each hour. In welfare homes, the children heard 178 utterances per hour (p. 4).” Since brain research supports the importance of verbal language to brain development, it proposes that the poorer the children are, the dumber they are. In the final analysis, we seem to fall so easily into the trap of focusing on families as being deficient either because they support the education of their children too much or not enough.

I wonder what would happen if we could put groups of parents from different backgrounds together in an environment where it is safe emotionally for both? Let us all take a look together at what they are doing instead of what they are not. For instance, what about the example of the parents at Prescott and Colton? Although, parents at Colton portrayed discomfort with the school environment, most often as a result of their own educational experiences, they also seemed to have a respect for the total child and the need for balance in a child’s life. One mother whose son spent plenty of after school time in the open air on his bike and with friends, said, “My job is here at home. My job is to raise him, to teach him manners, get him dressed and get him to school, to make sure that he is happy. Now her [the teacher's] part, the school's part, is to teach him to learn (Lareau, 1987, p. 82). “The sometimes overzealous Prescott parents might be able to learn a thing or two from the Colton parents about a balanced childhood and the impact it has on success in life. And if the right environment could be achieved, the Colton parents could learn how to access the teacher, the educational system in general, advocate for their child and that they do in fact have a valuable role in the home-school partnership. Again, what if as educators we found a way to focus both sets of parents attention on what learning is going on at home? Prescott-type parents might learn to relax and trust the process of balanced learning more, and Colton-type parents might discover all the valuable learning at home that is happening, even if they feel ill prepared to help their child with formalized mathematics.

The key is for teachers to remember that involvement in a child’s education takes many valuable forms and looks different for each family. Our current definitions of the role of the home and the school in the education of the child support structures that not only give parents the responsibility for promoting artificial learning but also devalue the contributions that they do and can make. Since parents are not bound by the four walls of the classroom as we teachers often are, perhaps it would be a better use of their capacity and skill for us to support the authentic learning that inevitably happens naturally at home rather than asking them to support improving their child’s homework packet grade or spelling test results.

A Fundamental shift from seeing what isn’t happening to seeing what is

Along with my partner teachers, we began to ask the following questions: What if we shifted our vision to see what learning is happening in homes instead of what isn’t? What if we changed the way we define authentic learning, school and staff to extend beyond the view embedded heavily in the Industrial Revolution, thus making the walls of the school more permeable? What if our definition of teacher included parents? The impact of networking parents from across cultures together with protocols that provide a safe space for parents to learn from and share with each other could be far reaching. Imagine a learning community where parents realized how valued their contributions were to a school or classroom and their involvement was not solely defined by how many minutes they read with their child each night or how often they practiced a spelling test? Would parents across all cultures exhibit a more balanced, joyful involvement if they had a more vested interest in the development of the program; if we actually taught in a method that was relevant to the reality of their world, and how might this address equity better than anything we could come up with on our own as educators? We spend so much time trying to differentiate education to meet the needs of each child. There is only one teacher in the classroom trying to do this for 20 plus students. But each parent only needs to differentiate for one child in that same classroom. Who better qualified or more of an expert on a child than the parents?

The challenge becomes that we often don’t honestly see parents as qualified. We look to the few cases of seemingly disconnected or ineffective parents that we have all dealt with over the years and internally cite this as a reason to avoid a fundamental shift in our approach. But the number of involved, loving parents is a far greater percentage than the number of parents to whom we must refer to child protective services. It’s getting more and more challenging to equitably prepare children for the world they are destined to inherit. We must take the risk and define a new partnership between home and school in order to accomplish our task.

This begins with redefining the way we see learning and changing our view of parent’s ability to teach their own children. In Daniel Quinn’s My Ishmael (1997), he explores the development and purpose of our current concept of school and cautions educators to remain in a humble posture of learning in order to avoid the conclusion that ‘experts’ in Quinn’s example came to, which was that parents do not know what is best for their children. Quinn uses the example of birds teaching their young to migrate as a metaphor for the trappings of our educational system today. In it, the expert birds interfere with the natural learning process of the parents teaching their young chicks, and then finally come to the conclusion that, “ordinary parents were not in fact qualified to teach their children anything as complex as migratory science (p. 156).” As we move forward in designing equitable, meaningful and progressive learning environments for the next generations, it is critical to avoid being influenced by any residue of a mindset that sees parents of any background as incapable. In fact it is by collaborating more closely with parents; by viewing them as colleagues that we will create a common framework, so that the changes we implement will have a lasting, relevant and equitable impact on society. In this respect, I cite an inspirational quote from the Selections of the Writings of Abdu’l-Baha (1978) regarding education.

Education cannot alter the inner essence of a man, but it doth exert tremendous influence, and with this power it can bring forth from the individual whatever perfections and capacities are latent within him. A grain of wheat, when cultivated by the farmer, will yield a whole harvest, and a seed, through the gardener’s care, will grow into a great tree. Thanks to a teacher’s loving efforts, the children of the primary school may reach the highest levels of achievement; indeed, his benefactions may lift some child of small account to an exalted throne (p.132).

This quote speaks to the varied capacities in children. In fact, an effective curriculum of instruction must reflect, in its content and process, this variation not only of capacity, but also of interest. Ultimately, it is the interest which drives the learning and it is the parents who can help us connect to the interest. In more recent times, Deci’s research (2008) shows how critical autonomous motivation is across all cultures to overall psychological health and well-being (p.183). Furthermore, Deci’s, Self-Determination Theory reminds us as educators that students are most motivated when the questions come from them. Our students need us to hear the burning questions in their hearts and not judge them, just honor their questions, help them develop and find the answers, even when they don’t seem connected to the content or skills we feel compelled to cover during the course of the year. The same holds true for the parents of these children. The challenge for us as teachers in the classroom is as Fisher (2009) put it when talking about doing puppet shows with high school students, it can be risky because, “The learning isn’t always immediately visible (p.2).” Developing the curriculum with parents and students can sometimes feel challenging because it must balance both individual and group needs. We must keep in mind that children’s capacities are vast and that the purpose of education is the realization of their potential. In the end, it becomes my job to listen, to facilitate the learning and even get out of the way of the learning sometimes. We are going to be more effective in achieving this aim if we work collaboratively with those most versed on the unique capacities and interests of each child, which of course are the parents.

A Culture of Collaboration: Balancing Parent Input, Student Voice and Teacher Vision

That is my motivation as I work with two other teachers to design a process that includes parent and student voice as critical components in the development of an equitable curriculum, one that addresses all of these needs. Through a series of parent workshops designed to expand narrow ideas about what constitutes cognitive learning and the role parents play in their children’s education, my hope is to implement protocols that will promote a strong collaboration between home and school, ultimately providing deeper learning for students. This year, we are focusing on parent and student voice in our program. Each teacher in the program met with each family in her class individually in order to foster a spirit of collaboration with them by listening to their goals and hopes, as well as to help them create a family learning plan that includes both parent and child input. Then we explained how these individual family learning plans would come together in a yearlong group plan that would include some of the elements of each of the plans. But before these meetings, it was important to establish a culture of collaboration. That was the purpose of the parent workshop that I designed and facilitated. The population I serve varies some in socioeconomic level, ethnicity and parenting philosophy. It is not as much as the difference that exists between the Prescott and Colton parents in Lareau’s research, perhaps. However, it is a place to begin to test out my desire to shift the balance of voice between home and school. In the workshop, I supported parents and students as they collaborated to begin the design of their personal family learning plans, which would be tuned later with me in individual family meetings. I wanted to see how I could assist parents instead of thinking about how they could assist me. It has been an interesting process so far and I am definitely taking a posture of learning, fully appreciating the flexibility my colleagues and I are afforded to attempt this pilot program at Innovations Academy. After each family created a personal learning plan, then it became my task to combine the common elements of their learning plans into a group learning experience for the year.

Each family contributed differently to the yearlong plan. Some families found great joy in creating a plan that reflected their academic priorities and goals. Already they have gone and made additions and revisions to the original learning plan and are sharing with me resources that they are finding for their child. I enjoy the email dialogues and Google doc sharing that is happening between us, as they share their excitement with me, and I provide resource suggestions or network them together as needed or requested. Although this sounds like a great deal of extra work for me, it really isn’t because these same parents are questioning the classroom curriculum much less. So far, there have been no complaints about the lack of academic rigor or what is not happening in the classroom. They seem busy experiencing the joys of learning collaboratively with their children at home. Also, they know that as many of their goals will be included in our year long plan as possible. The reality is that many of their goals are already embedded in our classroom design. We have just now had a conversation early in the year where I get to explain how. Often as educators, we spend energy using teacher talk to try to connect with parents and answer questions that they might not even have. It was very valuable for me to listen first; to hear the parents before I started talking about the classroom program so that what I said and how I said it meant something to them.

Other families have learning plans much more focused on social emotional growth and didn’t have any explicitly stated academic goals. For them, the academic goals were less and more open-ended, if stated at all. Sometimes, in a few of the categories, there is only one brief sentence that represents the child’s voice. For instance, on one family learning plan under the category of science, it says, “________wants to learn about as many spiders as possible so that he can find the one spider that can bite him and turn him into Spider Man!” This goal came directly from the child and will be an easy element of learning that I can include in the classroom during our garden project (minus the actual bite!). The communication with these families seems to flow easily. Hopefully, it is because they can see that I value their goals and have expressed excitement and appreciation for the learning that is going on at home. During our family meetings I was able to hear about all the wonderful unstructured opportunities for creative exploration that their children had at home and they were able to see that I value that as an educator.

The Workshop Process

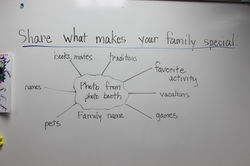

In the workshop agenda, I included a whole group brainstorming session, a chalk talk interspersed with a few getting- to- know- you movement games and a debrief as a whole group. First, parents and children consulted about different elements of a modified mandala, inspired by a model presented by Brent Cameron in Self-Design: Nurturing Genius through Natural Learning. The elements of the mandala I used in the workshop are only separated to encourage us to remember that a well-rounded education attends to all aspects of the multi-faceted individual; language arts, math/logic, science, social studies, life skills, physical fitness, creativity, spirit. In practice, these elements are integrated.

I asked parents and children to think about their family’s favorite activities and pastimes, things they did together. I shared with them a handout (appendix A) that highlighted examples of joyful learning that we don’t often think of in academic terms. Also, I gave them a template to begin outlining their thoughts in regards to their own learning plans.

Then as they shared their thoughts, I wrote down what they said under the categories of the mandala, paying close attention to the “academic” categories. The purpose of this brainstorming session was to illustrate how much learning in the subject areas that we are used to thinking of as ‘school’ is found in activities that families commonly do.

Second, parents and children moved in groups from table to table where I had a large sheet of paper with one of the categories from the mandala listed. Their task was to draw or write about what they might like to do or learn about in that particular category. Again, this was done is a chalk talk format. Students could illustrate rather than write. However, parents were also encouraged to be “the pencil” for their child as needed or requested. Dispersed throughout the rotations, which were timed, we did some movement activities together to keep young learners engaged and for everyone to laugh and become comfortable with each other. At the close of the brainstorming, we shared out some aha moments that we had. Parents commented that they appreciated hearing ideas from each other. In addition to broadening our definition of cognitive, academic learning, the ultimate purpose of the workshop was two-fold: to give families the space to begin developing their personal learning plan where the voices of all family members were honored and to establish a culture of collaboration between parent and teacher.

After the workshop, families met with me individually to further develop their personal learning plans, consider resources or mentors needed and to set tentative timelines, keeping in mind that a learning plan is a living document. Again, the purpose was to establish a spirit of collaboration. In addition, it was at this time that I utilized information from the personal learning plans to begin to design our collective year together. Each learning plan was created in Google docs and then shared with the family that authored it. At this point, I was a resource and facilitator of the goals that they prioritized. Essentially, I served as a critical friend to whom they could and can turn to with questions, concerns or for feedback. The process was extremely valuable to me because it gave me the opportunity to discover the learning styles of the families, as well as their hopes and goals. Hopefully, it gave them the venue to be heard and valued in the school community.

The Next Step: Expanding the Definition of Collaboration Even More

The next stage in the process will be another workshop mid-year, where parents will evaluate the progress of their learning plans. It is at this time that I want to facilitate a protocol where parents can bring a challenge or question about the implementation of their learning plan and get feedback from each other rather than just me. After the second workshop, I will have another round of individual meetings with each family. I am in the process of planning this workshop in collaboration with my colleagues and want it to be much more interactive between the participants than this first one. I hope that parents can begin to see themselves as colleagues not just with me, but also with each other.

But before I do, there are several things I want to consider, including the successes of this past workshop and the areas that I would like to improve. I have already debriefed with my critical friend and one other colleague to get feedback about the first workshop. They both were able to stop in to observe parts of the workshop, know what my goals are and have first-hand knowledge of the population I serve. Jill Keltner is serving as my critical friend this year. Jennifer Mercer is a Self-Design consultant and introduced me to Brent Cameron’s work. She has been instrumental in the adaptation of the mandala that I used in the workshop. Also, I am requesting input from my advisor, because Brett Peterson has extensive knowledge regarding facilitating protocols and can assist me with common challenges I might face in the upcoming parent workshop.

Some feedback from the debriefing of the first workshop and things to plan for the next time I give this one:

-

Parent voice was heard in this process. To increase student voice, they suggested that I use concrete objects associated with each category of the mandala. For instance, math manipulatives or games, cooking utensils at the math/logic table might help students connect to something they are interested in learning more about and help them vocalize their interests. The interspersed movement games kept the children engaged as well as utilizing the chalk talk format.

-

Provide more time at each station, but continue to time it because it gave structure to the activity.

-

I used a quilt that had different topics of study in each square. It represents the learning journey of one of my years of teaching kinder and is a stunning and inspiring creation to look at. It was used as a resource for children to point to what square most interested them and parents could discuss why with them. However, I could put the quilt at the beginning of the workshop and use it as a prop for the initial brainstorming. It was off to the side during the chalk talk and was not as valuable a resource as I would have liked simply because of its location.

-

I could invite students who have been co-designing their learning to come and lead part of the brainstorming or provide a panel for parents to ask questions.

-

I could add exit cards to the workshop so that I can get more involved and honest feedback.

-

The following are questions that I explored with Jill Keltner as I plan for the next workshop:

-

How to model the protocol whole group with children present: how to include them? I want to keep the process family-centered since many of the families have younger siblings at home. However, I also want to provide space for the parents to reflect peacefully.

-

Meaningful activities for children while parents are in small groups. What can they do in small groups or partnerships? How can they reflect and express their reflections? Again, I want student voice heard. However, this workshop is definitely more parent focused for my age group. As children get older they can participate more sentiently in their own education. Yet, I want even the youngest children to have the benefit of hearing their parents and teachers collaborate and to know that their voice is validated in the process.

-

Plan time for exit cards. I want to give more space for parents to give input and to do so anonymously will give me more valuable feedback...hopefully!

-

I would like to include time for parents to write a letter to their child or write a general reflection that includes observations surrounding growth the child has made, struggles they have overcome and/or honoring their achievements. This would give parents the space to honor the meaningful learning that is happening. Again, focusing the attention on what is versus what isn’t happening. This reflection time can also aid in the planning or editing of their personal learning plans. Perhaps, let them share out as they are comfortable because we always learn so much from hearing each other’s experience

In closing, one aspect that I noticed in the first workshop is the excitement that parents had about learning alongside their children. It was very inspiring. If education is, as W.B. Yeats is credited with saying, “…not the filling of a pail but the lighting of a fire.” then nowhere is that more evident than when watching a child and parent passionately discover something new together! It is truly a privilege to be a part of such a joyful learning journey. This has to have a positive impact on learning in the long run! After all, “In times of joy our intellect is keener….!” ~Abdu’l-Baha

Cameron, B. (2006).Self Design: Nurturing Genius through Natural Learning. Colorado. Sentient Publications

Deci, E. and Ryan, R. (2008). Self-determination theory: A macro theory of human motivation, development, and health. Canadian Psychology, 49, 3, 182-185.

Fisher, J. (2009). Exhibition Blues. UnBoxed, 3.

Gail, M. (1978). Selections of the Writings of Abu’l-Baha. Haifa, Israel. Baha’i Publishing Trust. (Original work published 1844-1921)

Lareau, A. Social Class Differences in Family-School Relationships: The Importance of Cultural Capital Sociology of Education, Vol. 60, No. 2 (Apr., 1987), pp. 73-85

Quinn, D. (1997). My Ishmael. New York. Bantam Books.

Tough, P. (2006). “What it takes to make a student.” NY Times Magazine, November 26, 2006.

As we define what it means to advocate for, nurture and sustain a school culture conducive to student learning and staff professional growth, it becomes necessary to first expand our definitions of school and staff. In traditional settings, we spend much time as educators talking about how to connect learning to the real world beyond the four walls of the classroom. Implicit in these discussions is the understanding that school is the building where students spend six or seven hours a day, Monday through Friday, under the supervision of expert staff hired to guide them and keep them safe while their parent/guardians are at work or otherwise engaged. In addition, these same hired educators spend time in professional development dedicated to learning pedagogies that hopefully will provide an equitable access to a quality education for all students. Sometimes, schools offer parent education classes or volunteer opportunities for parents to support the work of the teachers in the classrooms, since it is widely understood that student learning improves when the home-school connection is strong. In short, a school culture conducive to learning includes connection to the real world, staff willing to remain in a learning mode themselves and parent involvement. Currently, I am collaborating with two other teachers to create and implement a shared vision for a program designed to expand the definition of school to include any place where learning happens and staff to include parents as well as paid teachers. As part of the year long program, I am conducting a series of workshops designed to guide parents through the program and provide a structure where we (parents and teachers) enter into a partnership as co-teachers of their children. The following is a new definition of parental involvement, an explanation of a workshop I facilitated, along with reflections about the effectiveness of the strategies I tried and plans for the next workshop based upon my learning.

Parents As Colleagues

Establishing partnerships with a workshop at the beginning of the year

Slideshow (with captions) of Workshop

|  |  |

|---|---|---|

|  |  |

|  |  |

|  |